An Introduction to the Heart of the Operating System

At the very core of every Linux distribution—from a lightweight container image to a sprawling enterprise Linux Server—lies the Linux kernel. It is the foundational layer of the operating system, the master controller that facilitates communication between your software and the physical hardware. Conceived by Linus Torvalds in 1991, the kernel has evolved into one of the most significant and widely adopted open-source projects in history. It manages the system’s resources, including the CPU, memory, and peripheral devices, providing a stable and consistent abstraction layer for applications to run on. Understanding the kernel is not just an academic exercise; it’s a crucial skill for advanced Linux Administration, System Programming, and modern Linux DevOps practices. Whether you’re running Debian Linux, Red Hat Linux, or a custom build on an AWS Linux instance, the kernel is the silent, powerful engine driving it all. This article provides a comprehensive deep dive into the kernel’s architecture, practical programming with kernel modules, and the process of compiling your own custom version.

Deconstructing the Linux Kernel’s Core Components

The Linux kernel is often described as a monolithic kernel, meaning the entire operating system core runs in a single address space. However, its modern design is highly modular, allowing for drivers and features to be loaded or unloaded at runtime. This hybrid approach provides the performance of a monolithic design with the flexibility of a microkernel. Its primary responsibilities can be broken down into four key areas.

The Kernel’s Primary Responsibilities

- Process Management: The kernel is responsible for creating, scheduling, and terminating processes. It manages the CPU’s time, deciding which process gets to run and for how long, enabling multitasking.

- Memory Management: It allocates and deallocates memory for processes, manages virtual memory using techniques like paging and swapping, and ensures that one process cannot access the memory of another, providing crucial Linux Security.

- Device Drivers: The kernel contains a vast collection of drivers that act as translators between the hardware (like GPUs, network cards, and storage devices) and the software.

- System Calls and Filesystem Management: It provides a secure interface—the system call interface—for user-space applications to request services, such as file I/O or network communication. It also manages the Linux File System, handling file creation, deletion, and access control based on Linux Permissions.

Kernel Space vs. User Space

A fundamental concept in Linux is the separation between “kernel space” and “user space.” Kernel space is a protected memory area where the kernel and its drivers execute with unrestricted access to all hardware. User space is where all user applications (like your web browser, text editor, or a Python Scripting environment) run. This separation is a security mechanism; a crash in a user-space application will not bring down the entire system. The only way for a user-space program to perform a privileged action, like writing to a disk or opening a network socket, is to request it from the kernel via a system call.

Interacting with the Kernel: The /proc and /sys Filesystems

The kernel exposes a wealth of information and configuration options through virtual filesystems, primarily /proc and /sys. These are not real files on your disk but are generated on-the-fly by the kernel. You can interact with them using standard Linux Commands. For example, to check your current kernel version and the command line used to boot it, you can simply read from files in /proc.

# Display the running kernel version information

cat /proc/version

# Display the command line arguments passed to the kernel at boot time

cat /proc/cmdline

# List all block devices (like hard drives and partitions) known to the kernel

lsblkPractical Linux Kernel Programming: Your First Module

One of the most powerful features of the Linux kernel is its support for Loadable Kernel Modules (LKMs). An LKM is a piece of code that can be loaded into and unloaded from the kernel on demand, without rebooting the system. This is how most device drivers, filesystem drivers, and other specialized features are implemented. Writing a simple LKM is an excellent exercise in Linux Development and System Programming.

Writing a “Hello, World” LKM in C

Let’s create a basic “Hello, World!” kernel module. This module will simply print a message to the kernel log buffer when it’s loaded and another message when it’s unloaded. You’ll need the kernel headers for your running kernel and build tools like gcc and make installed. On a Debian Linux or Ubuntu Tutorial system, you can install them with sudo apt install build-essential linux-headers-$(uname -r).

Create a file named hello_kernel.c:

#include <linux/init.h>

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/kernel.h>

// Metadata for the module

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("Your Name");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("A simple Hello World Linux Kernel Module.");

MODULE_VERSION("0.1");

// This function is called when the module is loaded

static int __init hello_init(void) {

printk(KERN_INFO "Hello, Kernel World!\n");

return 0; // A non-zero return indicates that init_module failed

}

// This function is called when the module is removed

static void __exit hello_exit(void) {

printk(KERN_INFO "Goodbye, Kernel World!\n");

}

// Register the init and exit functions

module_init(hello_init);

module_exit(hello_exit);Compiling and Loading Your Module

To compile this C code into a kernel module, you need a special `Makefile`. The kernel’s build system handles the complex flags and linking. Create a file named `Makefile` in the same directory:

obj-m += hello_kernel.o

all:

make -C /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build M=$(PWD) modules

clean:

make -C /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build M=$(PWD) cleanNow, open your Linux Terminal and run the following commands:

# Compile the module

make

# Load the module into the kernel (requires root privileges)

sudo insmod hello_kernel.ko

# Check the kernel log for our message

dmesg | tail

# See the loaded module

lsmod | grep hello_kernel

# Unload the module

sudo rmmod hello_kernel

# Check the kernel log again for the goodbye message

dmesg | tailYou’ve just successfully written, compiled, and run code directly inside the Linux kernel! This is the foundation for writing device drivers and extending kernel functionality.

Advanced Kernel Management: Compiling from Source

While most users of distributions like Fedora Linux or CentOS rely on pre-compiled kernels provided by their package manager, there are compelling reasons to compile your own kernel from source. This is a common task for embedded systems developers, performance enthusiasts, and system administrators who need to enable specific features or apply security patches not yet available in official builds.

Why Compile Your Own Kernel?

- Performance Tuning: You can disable unused drivers and features, resulting in a smaller, faster-loading kernel that consumes less memory.

- Hardware Support: Enable experimental drivers or support for very new or obscure hardware.

- Security Hardening: Apply custom security patches or enable specific kernel hardening options (e.g., strengthening SELinux defaults) that are not enabled by default.

- Learning: The process itself is an invaluable learning experience for anyone serious about Linux Administration or development.

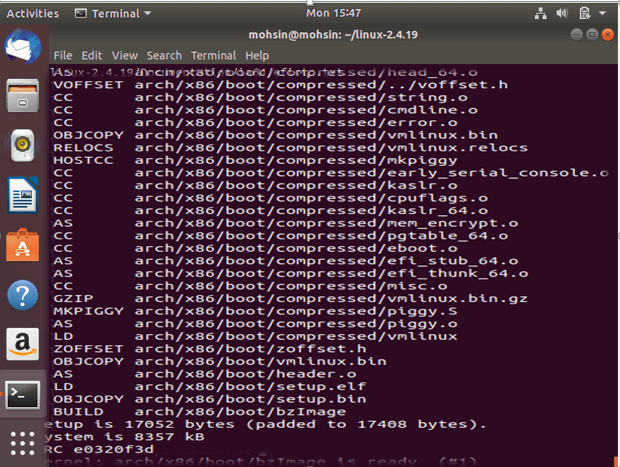

The Kernel Compilation Workflow

The process generally follows these steps:

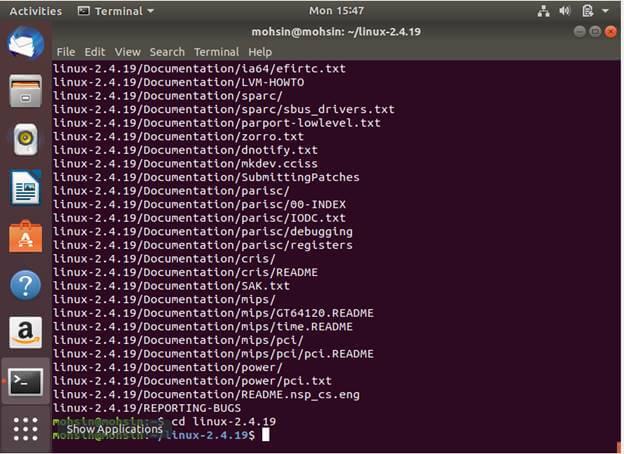

- Download the Source Code: Get the latest stable kernel source from kernel.org.

- Configure: This is the most critical step. You configure which features, drivers, and options to include in your build. The

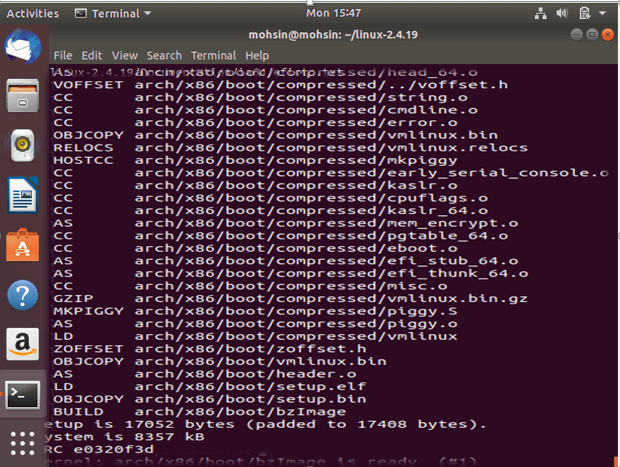

make menuconfigcommand provides a text-based user interface for this. - Build: Compile the source code into a kernel image (

bzImage) and the configured modules. - Install: Copy the new kernel, modules, and associated files to the correct locations and update the bootloader (GRUB).

This Bash Scripting example outlines the core commands for the build and install process on a Debian-based system. It’s a simplified illustration of the steps involved in Linux Automation for this task.

#!/bin/bash

# A simplified script to demonstrate kernel compilation steps

# WARNING: Do not run this script without understanding each command.

# It is for educational purposes only.

# Exit on any error

set -e

# Number of CPU cores to use for compilation

# Using nproc is a good way to get the number of available processing units

COMPILE_JOBS=$(nproc)

echo "--- Starting Kernel Compilation ---"

# 1. Configure the kernel

# It's best to start with your current config as a base

cp /boot/config-$(uname -r) .config

# Open the text-based menu to customize options

make menuconfig

# 2. Build the kernel and modules

# The -j flag specifies the number of parallel jobs

echo "Building kernel with ${COMPILE_JOBS} jobs..."

make -j${COMPILE_JOBS}

# 3. Install the modules

echo "Installing modules..."

sudo make modules_install

# 4. Install the kernel

echo "Installing the new kernel..."

sudo make install

echo "--- Kernel Compilation Complete ---"

echo "Reboot your system and select the new kernel from the GRUB menu."Best Practices for Kernel Management and Security

Managing the kernel requires a careful and considered approach. A misconfiguration or a buggy module can lead to system instability or security vulnerabilities.

Keeping Your Kernel Updated

For the vast majority of users and administrators, the best practice is to stick with the kernel provided by your Linux Distributions‘s package manager (apt, dnf, pacman). These kernels are heavily tested and patched for known vulnerabilities. Regularly run system updates to ensure you have the latest security fixes. Only venture into manual compilation if you have a specific, well-understood need.

Kernel Hardening and Security

The kernel is the front line of Linux Security. Modern kernels include numerous security mechanisms. Security-Enhanced Linux (SELinux) and AppArmor are Mandatory Access Control (MAC) systems implemented as kernel modules that can enforce fine-grained security policies. When compiling a kernel, you can enable additional hardening options to make it more resilient to attacks.

Monitoring Kernel Performance and Health

Effective System Monitoring is key to maintaining a healthy server. The kernel provides the raw data that monitoring tools use.

dmesg: The kernel ring buffer is your first stop for debugging hardware and driver issues.top/htop: These classic Linux Utilities read process and system load information directly from the/procfilesystem, which is populated by the kernel. They are indispensable for Performance Monitoring.perf: A powerful and complex Linux Tools suite for in-depth performance analysis, allowing you to trace kernel and application events to pinpoint bottlenecks.

Conclusion: The Foundation of Your Linux Journey

The Linux kernel is far more than just a piece of software; it’s the robust, flexible, and powerful foundation upon which the entire Linux ecosystem is built. From managing processes on a simple Linux Web Server running Nginx to orchestrating complex workloads in a Kubernetes Linux cluster, the kernel is the unsung hero. We’ve journeyed from its core concepts of process and memory management to the practical, hands-on experience of writing a kernel module and the advanced task of custom compilation. By understanding how to interact with, program for, and manage the kernel, you unlock a deeper level of control and insight into your systems. As a next step, consider exploring the extensive documentation within the kernel source code itself, or dive into the specifics of a subsystem that interests you, such as Linux Networking or the file system layer.