In the modern landscape of high-performance computing and automated systems, security is no longer just about firewalls and encryption keys; it is about architecture. As we integrate more autonomous agents and complex logic into our infrastructure, the concept of containment becomes paramount. At the heart of this containment strategy lies the fundamental, yet often misunderstood, system of Linux File Permissions. Whether you are managing a massive Linux Server farm running Ubuntu or Red Hat Linux, or simply hardening a local development environment, understanding how to isolate processes and data is the first line of defense.

The Linux Operating System handles security through a robust discretionary access control (DAC) model. Every file, directory, and process is owned by a user and a group, and access is strictly dictated by permission bits. This mechanism is what allows a System Administrator to treat specific applications—such as a web server or an AI model—as restricted entities, effectively placing them in a digital cell where they can only touch what they are explicitly allowed to touch. This article will serve as a comprehensive Linux Tutorial, moving from core concepts to advanced programmatic control using Python Scripting and Access Control Lists (ACLs).

Section 1: The Anatomy of Linux Permissions

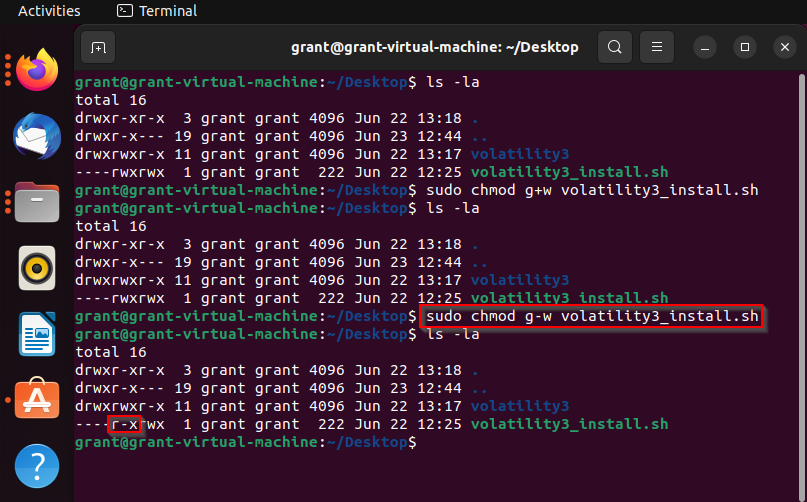

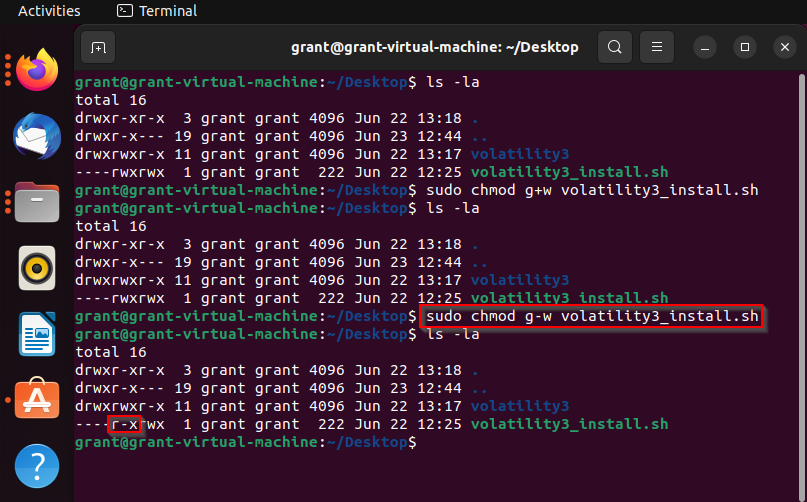

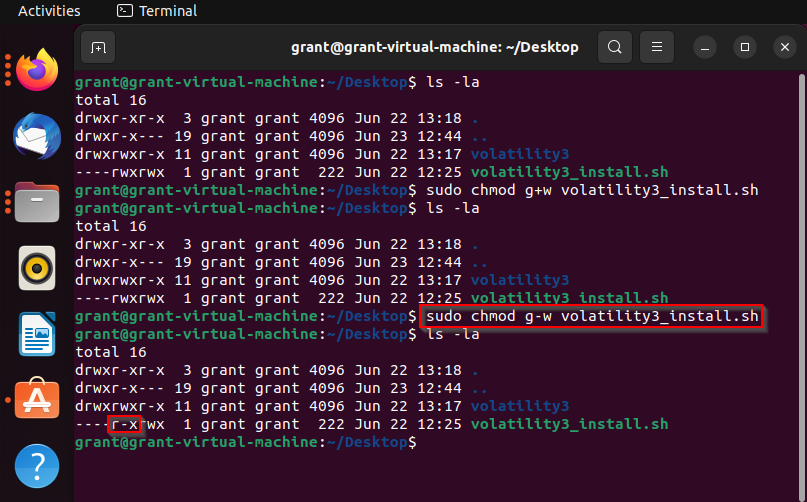

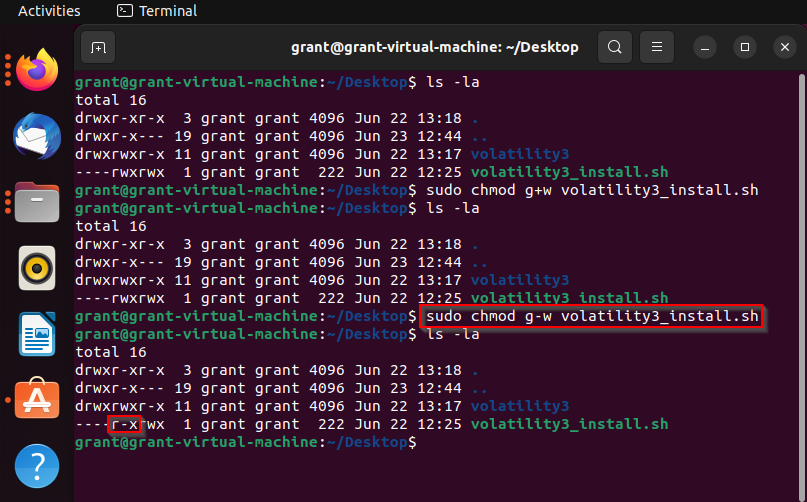

To master Linux Security, one must first be fluent in the language of the Linux Terminal. When you run the ls -l command, you are presented with a string of characters that defines the security posture of a file. This string, such as -rwxr-xr--, represents the permission modes for three distinct categories: the User (owner), the Group, and Others (everyone else).

Understanding Read, Write, and Execute

The permissions are broken down into triads. The first character indicates the file type (- for file, d for directory, l for link). The following nine characters represent the permissions:

- Read (r): Allows viewing the contents of a file or listing the contents of a directory.

- Write (w): Allows modifying a file or creating/deleting files within a directory.

- Execute (x): Allows running a file as a program or entering/traversing a directory.

In Linux Administration, these are often represented numerically (Octal notation): Read=4, Write=2, Execute=1. A permission set of rwx equals 7, while r-x equals 5. This is crucial when configuring Linux Web Servers like Apache or Nginx, where you typically want the web user to read files but never write to the configuration directories.

Below is a Bash Scripting example demonstrating how to analyze and modify these permissions using standard Linux Commands.

#!/bin/bash

# Create a dummy directory for a specific service (e.g., an isolated agent)

mkdir -p /opt/isolated_agent/data

# Create a configuration file

touch /opt/isolated_agent/config.json

# Check initial permissions

echo "Initial Permissions:"

ls -l /opt/isolated_agent/config.json

# LOCKDOWN PROCEDURE

# 1. Change owner to a specific service user (assuming user 'agent_user' exists)

# sudo useradd -m agent_user

# sudo chown agent_user:agent_group /opt/isolated_agent/config.json

# 2. Set permissions:

# Owner (agent_user) gets Read/Write (4+2=6)

# Group gets Read only (4)

# Others get NO access (0)

chmod 640 /opt/isolated_agent/config.json

echo "Secured Permissions:"

ls -l /opt/isolated_agent/config.json

# 3. Directory Traversal Security

# Ensure only the owner can traverse the directory

chmod 700 /opt/isolated_agent

echo "Directory Permissions:"

ls -ld /opt/isolated_agentThis basic isolation is critical. If you are running Python Automation scripts or Docker containers, ensuring that the process running inside the container cannot read /etc/shadow or write to /usr/bin is enforced by these bits.

Section 2: Advanced Permissions and Special Bits

Standard permissions cover 90% of use cases, but complex Linux System Administration requires more nuance. This is where special permission bits come into play: SUID, SGID, and the Sticky Bit. These are powerful tools but represent significant security risks if misconfigured.

SUID (Set User ID)

When the SUID bit is set on an executable, the file runs with the permissions of the file’s owner, not the user who launched it. This is how the passwd command works; it allows a standard user to update the root-owned password database. However, in the context of Linux Security, unauthorized SUID binaries are a primary vector for privilege escalation.

SGID and Sticky Bit

The SGID bit on a directory forces new files created inside to inherit the group of the directory, rather than the user’s primary group. This is essential for shared team directories in Linux DevOps environments. The Sticky Bit (seen as a t at the end of permissions) prevents users from deleting files they don’t own, even if they have write access to the directory (standard behavior for /tmp).

Here is a script useful for Linux Monitoring and auditing. It scans the filesystem for SUID binaries, which is a critical step in hardening CentOS, Debian Linux, or Arch Linux systems.

#!/bin/bash

# AUDIT SCRIPT: Finding Potentially Dangerous SUID Files

# This helps verify that only authorized binaries have elevated privileges.

LOG_FILE="/var/log/suid_audit.log"

echo "Starting SUID Audit at $(date)" > $LOG_FILE

# Find files with SUID bit set (-perm /4000)

# -type f : Only look for files

# 2>/dev/null : Suppress permission denied errors for the finder itself

echo "Scanning system for SUID binaries..."

find / -perm /4000 -type f -exec ls -ld {} \; 2>/dev/null | while read line; do

echo "FOUND: $line" | tee -a $LOG_FILE

# Simple heuristic: Check if the file is world-writable (EXTREMELY DANGEROUS)

if [[ "$line" == *"w-"* && "$line" == *"-rws"* ]]; then

echo "CRITICAL WARNING: World-writable SUID file detected!" | tee -a $LOG_FILE

fi

done

echo "Audit complete. Check $LOG_FILE for details."Regularly running such audits is a best practice in Linux Server management. If an isolated process manages to create a SUID binary, it could break out of its containment.

Section 3: Programmatic Control with Python

While Bash Scripting is excellent for quick tasks, modern Linux DevOps relies heavily on Python Scripting for automation, configuration management (like Ansible), and system orchestration. Python’s os and stat modules provide granular control over file permissions, allowing developers to build security directly into their applications.

Imagine you are building a Python Linux application that handles sensitive user data. You need to ensure that every time a data file is generated, it is immediately locked down. Relying on the default umask is risky; explicit permission setting is safer.

The following example demonstrates how to use Python to manage permissions and ownership, a technique applicable in Cloud Linux environments like AWS Linux or Azure Linux.

import os

import stat

import pwd

import grp

def secure_file_creation(file_path, content, user_name, group_name):

"""

Creates a file with strict permissions and specific ownership.

Simulates a 'jail' for data files.

"""

try:

# 1. Write the content

with open(file_path, 'w') as f:

f.write(content)

print(f"File created at {file_path}")

# 2. Get UID and GID from names

uid = pwd.getpwnam(user_name).pw_uid

gid = grp.getgrnam(group_name).gr_gid

# 3. Change Ownership (chown)

# Note: This usually requires root privileges or CAP_CHOWN capability

os.chown(file_path, uid, gid)

print(f"Ownership changed to {user_name}:{group_name}")

# 4. Set Permissions (chmod)

# Read/Write for Owner (6), No access for Group/Others (00)

# stat.S_IRUSR | stat.S_IWUSR equates to 600 octal

permissions = stat.S_IRUSR | stat.S_IWUSR

os.chmod(file_path, permissions)

# Verify

file_stat = os.stat(file_path)

print(f"Permissions set to: {oct(file_stat.st_mode)[-3:]}")

except PermissionError:

print("Error: Insufficient privileges to change ownership.")

except KeyError:

print(f"Error: User {user_name} or Group {group_name} not found.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An error occurred: {e}")

# Example Usage (Run as root for chown to work)

# secure_file_creation('/var/secure_data/secret.txt', 'Top Secret', 'www-data', 'www-data')This approach is vital for System Programming. By explicitly defining permissions within the code, you reduce the reliance on external configuration states, making your application more resilient and secure by design.

Section 4: ACLs and Best Practices for Containment

Sometimes, the standard User-Group-Other model is too restrictive. What if you need the apache user to read a file, the developer user to write to it, and the backup user to only read it, all without opening it up to the world? This is where Access Control Lists (ACLs) come in. ACLs provide a flexible permission mechanism essential for complex Linux Networking and file sharing environments.

Implementing ACLs

Tools like setfacl and getfacl allow you to assign permissions to specific users or groups beyond the file’s owner. This is often used in conjunction with SELinux (Security-Enhanced Linux) on distributions like Fedora Linux and CentOS to provide deep defense.

# Check current ACLs

getfacl /var/www/html/project

# Grant the user 'intern' read-only access to a file owned by root

# without changing the file's owner or group.

setfacl -m u:intern:r /var/www/html/project/config.php

# Remove the permission

setfacl -x u:intern /var/www/html/project/config.php

# Set a default ACL so all new files created in a directory

# automatically give 'dev_team' rwx access.

setfacl -d -m g:dev_team:rwx /var/www/html/projectBest Practices for System Hardening

To effectively contain processes and users, adhere to these Linux System Administration best practices:

- Principle of Least Privilege: Always grant the absolute minimum permissions required. If a Python Script only needs to read a config file, do not give it write access.

- Isolate Identities: Never run services as

root. Create specific users for specific tasks (e.g.,ai_agent_user,db_user). This ensures that if the service is compromised, the attacker is trapped in a user account with limited scope. - Secure the Mount Points: When performing Linux Disk Management, mount partitions with

noexec,nosuid, andnodevwhere possible. For example, a/tmppartition should often be mounted withnoexecto prevent malware from running there. - Monitor Changes: Use Linux Tools like

auditdor file integrity monitoring (FIM) to detect when permissions on critical files change unexpectedly. - Container Awareness: In Kubernetes Linux environments, ensure that the User ID (UID) inside the container maps to a non-privileged user on the host.

Conclusion

In the era of autonomous software and increasing cyber threats, trusting a process to behave correctly is not a strategy; it is a vulnerability. By leveraging the robust architecture of Linux File Permissions, ACLs, and user isolation, we can build systems that enforce security through structure rather than hope. Whether you are writing C Programming Linux applications or managing a Linux Cloud infrastructure, treating every process like a contained entity ensures that a breach in one area does not lead to a total system compromise.

Start auditing your systems today. Check your SUID bits, review your user groups, and script your permission enforcement. Security is an active process, and in the Linux world, the file system is your most powerful control plane.