In the realm of Linux Administration and System Programming, few concepts are as fundamental yet frequently misunderstood as the Linux File System. Whether you are managing a high-traffic Linux Web Server running Nginx or Apache, orchestrating containers with Kubernetes Linux, or performing low-level C Programming Linux tasks, the file system is the bedrock upon which your data resides. The mantra “everything is a file” is central to the UNIX philosophy, implying that documents, directories, hardware devices, and even system processes are represented as file descriptors.

However, a static understanding of directory hierarchies is no longer sufficient for modern DevOps and Linux Security. As infrastructure becomes more immutable and automated, the concept of “configuration drift”—where the actual state of a server diverges from its intended state due to manual changes, updates, or malicious activity—becomes a critical concern. This article provides a comprehensive technical exploration of the Linux File System, moving from core architectural concepts to advanced integrity monitoring and Python Automation for drift detection.

The Architecture of the Linux File System

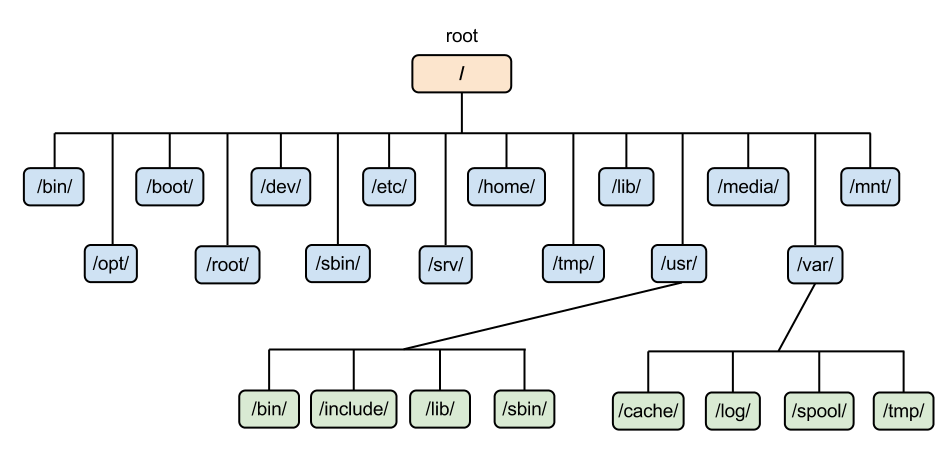

To master Linux Disk Management, one must look beyond the visual tree structure and understand the underlying mechanisms that the Linux Kernel uses to manage data. This involves the Virtual File System (VFS), Inodes, and the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS).

The Virtual File System (VFS) and Inodes

The VFS is an abstraction layer within the kernel that allows applications to interact with different file system types (ext4, XFS, Btrfs, NFS) transparently. When a user runs a command in the Linux Terminal, the VFS translates that request into the specific instructions required by the underlying storage driver.

At the heart of this system is the Inode (Index Node). An inode is a data structure that stores metadata about a file, excluding its name and actual data content. This metadata includes:

- File size and physical location on the disk blocks.

- Owner (User ID) and Group (Group ID).

- File Permissions and access control modes.

- Timestamps (creation, modification, access).

- Link count (how many filenames point to this inode).

A common pitfall in Linux Server management is running out of inodes before running out of disk space, particularly on servers hosting millions of small files (common in Linux Web Server caching or mail queues). Understanding how to query and monitor inode usage is a vital System Administration skill.

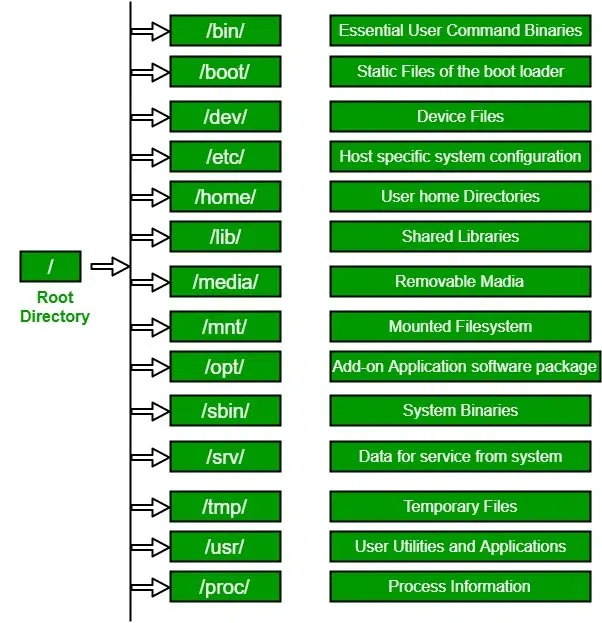

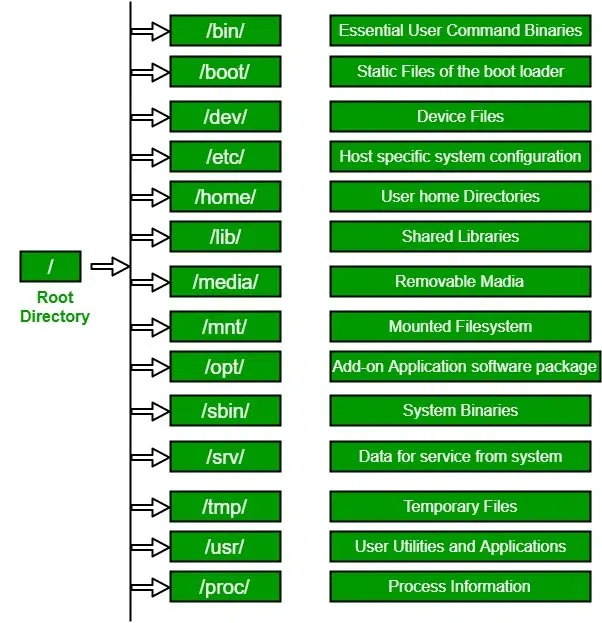

Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS)

Whether you are using Ubuntu Tutorial guides, Debian Linux, Red Hat Linux, or Arch Linux, the directory structure generally follows the FHS. Key directories include:

/etc: System-wide configuration files./var: Variable data files (logs, databases like MySQL Linux or PostgreSQL Linux)./proc: A pseudo-filesystem providing an interface to kernel data structures./dev: Device files (e.g.,/dev/sda).

Below is a Bash Scripting example designed to audit disk usage, specifically looking for directories consuming high inode counts, which can indicate application drift or log spamming.

#!/bin/bash

# Linux File System Audit Tool

# Checks for disk usage and Inode consumption

TARGET_DIR="/var"

THRESHOLD=80

echo "Starting File System Audit on $TARGET_DIR..."

# Check Disk Usage

USAGE=$(df -h "$TARGET_DIR" | awk 'NR==2 {print $5}' | sed 's/%//')

if [ "$USAGE" -gt "$THRESHOLD" ]; then

echo "[WARNING] Disk usage is critical: ${USAGE}%"

else

echo "[OK] Disk usage is normal: ${USAGE}%"

fi

# Check Inode Usage specifically

echo "Analyzing Inode usage in top-level subdirectories..."

for dir in $(find "$TARGET_DIR" -maxdepth 1 -type d); do

# Count files inside (using inodes)

COUNT=$(find "$dir" | wc -l)

if [ "$COUNT" -gt 10000 ]; then

echo "[ALERT] High inode count in $dir: $COUNT files"

fi

done

echo "Audit Complete."Permissions, ACLs, and Security Auditing

Linux Security relies heavily on the permission model. The standard rwx (read, write, execute) bits for User, Group, and Others are the first line of defense. However, in complex environments involving Linux Users and shared resources, standard permissions often fall short.

Executive leaving office building – Exclusive | China Blocks Executive at U.S. Firm Kroll From Leaving …

Advanced Permissions and ACLs

Beyond standard permissions, administrators must understand:

- SUID (Set User ID): Allows a user to execute a file with the permissions of the file owner (often root). This is a major security risk if not monitored.

- SGID (Set Group ID): Ensures new files created in a directory inherit the group ownership of that directory, crucial for shared project folders.

- Sticky Bit: Prevents users from deleting files they don’t own in a shared directory (e.g.,

/tmp).

For more granular control, Access Control Lists (ACLs) allow you to grant permissions to specific users or groups beyond the primary owner. Tools like getfacl and setfacl are essential here.

Auditing Permissions with Python

Configuration drift often manifests as permissions becoming too loose over time. Using Python Scripting for Python System Admin tasks allows for sophisticated auditing. The following script scans a directory for “world-writable” files and SUID binaries, which are prime targets for Linux Hacking exploitation.

import os

import stat

import sys

def audit_permissions(start_path):

print(f"--- Auditing Permissions in {start_path} ---")

for root, dirs, files in os.walk(start_path):

for name in files:

filepath = os.path.join(root, name)

try:

file_stat = os.stat(filepath)

mode = file_stat.st_mode

# Check for World Writable (Security Risk)

if mode & stat.S_IWOTH:

print(f"[RISK] World Writable: {filepath}")

# Check for SUID bit (Potential Privilege Escalation)

if mode & stat.S_ISUID:

print(f"[ALERT] SUID Bit Set: {filepath}")

except PermissionError:

# Common when scanning system dirs without root

continue

except FileNotFoundError:

continue

if __name__ == "__main__":

target = sys.argv[1] if len(sys.argv) > 1 else "/etc"

audit_permissions(target)File Integrity Monitoring and Drift Detection

One of the most insidious issues in Linux Server management is silent file modification. This “drift” can occur at the file level (configuration changes), process level, or even kernel module level. While tools like Ansible can enforce configuration, they typically run on a schedule. Real-time or on-demand integrity checking is required to detect unauthorized changes or corruption.

Cryptographic Hashing for Integrity

To ensure that critical binaries (like /bin/ls, /bin/bash) or configurations (/etc/ssh/sshd_config) haven’t been tampered with, we use cryptographic hashing. By generating a SHA-256 hash of a file and comparing it to a known “good” baseline, we can detect even a single bit of change.

This approach is fundamental to Linux Security and is often implemented by tools like AIDE or Tripwire. However, understanding how to build a lightweight File Integrity Monitor (FIM) using Python Automation provides deeper insight into how these systems work.

import hashlib

import os

import json

import time

BASELINE_FILE = "fs_baseline.json"

MONITOR_DIRS = ["/etc/nginx", "/etc/ssh"]

def calculate_hash(filepath):

"""Returns SHA256 hash of a file."""

sha256_hash = hashlib.sha256()

try:

with open(filepath, "rb") as f:

# Read in chunks to handle large files efficiently

for byte_block in iter(lambda: f.read(4096), b""):

sha256_hash.update(byte_block)

return sha256_hash.hexdigest()

except (IOError, OSError):

return None

def create_baseline():

"""Creates a snapshot of file hashes."""

baseline = {}

print("Creating system baseline...")

for directory in MONITOR_DIRS:

for root, _, files in os.walk(directory):

for file in files:

path = os.path.join(root, file)

file_hash = calculate_hash(path)

if file_hash:

baseline[path] = file_hash

with open(BASELINE_FILE, 'w') as f:

json.dump(baseline, f)

print(f"Baseline saved to {BASELINE_FILE}")

def check_integrity():

"""Compares current state against baseline."""

if not os.path.exists(BASELINE_FILE):

print("No baseline found. Run creation first.")

return

with open(BASELINE_FILE, 'r') as f:

baseline = json.load(f)

print("Checking integrity...")

drift_detected = False

for filepath, stored_hash in baseline.items():

if not os.path.exists(filepath):

print(f"[DELETED] File missing: {filepath}")

drift_detected = True

continue

current_hash = calculate_hash(filepath)

if current_hash != stored_hash:

print(f"[CHANGED] Integrity violation: {filepath}")

drift_detected = True

if not drift_detected:

print("System Integrity Verified: No drift detected.")

# Example usage logic

if __name__ == "__main__":

# In a real scenario, use CLI args to switch modes

if not os.path.exists(BASELINE_FILE):

create_baseline()

else:

check_integrity()Advanced Storage Management: LVM and RAID

For enterprise Linux Distributions like CentOS, Fedora Linux, or Red Hat Linux, static partitioning is rarely sufficient. Administrators utilize LVM (Logical Volume Manager) and RAID to manage storage dynamically.

Logical Volume Manager (LVM)

Executive leaving office building – After a Prolonged Closure, the Studio Museum in Harlem Moves Into …

LVM abstracts physical disks into “Volume Groups,” from which “Logical Volumes” are carved out. This allows for resizing partitions on the fly without unmounting (in some cases) or system downtime. It is a critical component of Linux Disk Management.

Key LVM concepts include:

- PV (Physical Volume): The raw disk or partition.

- VG (Volume Group): A pool of storage created from PVs.

- LV (Logical Volume): The mountable partition created from the VG.

LVM also supports snapshots, which are invaluable for Linux Backup strategies before performing risky updates or Linux Automation tasks via Ansible. Below is a shell snippet demonstrating how to automate the creation of a snapshot before a system update.

#!/bin/bash

# LVM Snapshot Automation for Safe Updates

VG_NAME="vg_system"

LV_NAME="lv_root"

SNAPSHOT_NAME="root_snap_$(date +%Y%m%d)"

SNAPSHOT_SIZE="1G"

echo "Checking Volume Group space..."

FREE_SPACE=$(vgs --noheadings -o vg_free_count $VG_NAME)

if [ -z "$FREE_SPACE" ]; then

echo "Error: Volume Group $VG_NAME not found."

exit 1

fi

echo "Creating LVM snapshot: $SNAPSHOT_NAME"

lvcreate -L $SNAPSHOT_SIZE -s -n $SNAPSHOT_NAME /dev/$VG_NAME/$LV_NAME

if [ $? -eq 0 ]; then

echo "Snapshot created successfully."

echo "Proceeding with system update..."

# yum update -y or apt-get upgrade -y

else

echo "Failed to create snapshot. Aborting update."

exit 1

fiBest Practices and Optimization

Maintaining a healthy Linux file system requires a mix of proactive monitoring, security hardening, and performance tuning. Here are key best practices for modern Linux DevOps environments:

1. Mount Options and Security

Edit your /etc/fstab to apply security restrictions to specific partitions. For example, the /tmp directory should often be mounted with noexec (prevent binary execution) and nosuid (prevent SUID bits). This hardens the system against common exploits.

2. Monitoring and Alerting

Executive leaving office building – Exclusive | Bank of New York Mellon Approached Northern Trust to …

Use tools like htop, the top command, and iotop to monitor I/O wait times. High I/O wait indicates a bottleneck in the file system. For enterprise monitoring, integrate System Monitoring tools like Prometheus or Nagios to track disk space and inode usage trends over time.

3. Immutable Infrastructure

In Docker Tutorial and Kubernetes Linux contexts, prefer immutable file systems where possible. Use Container Linux principles where the root file system is read-only, and writable data is offloaded to external volumes or databases. This eliminates configuration drift at the root level entirely.

Conclusion

The Linux File System is a complex, hierarchical beast that serves as the nervous system of any Linux Server. From the metadata stored in inodes to the dynamic flexibility of LVM, understanding these layers is non-negotiable for effective System Administration. However, as systems scale, manual oversight becomes impossible. The risk of configuration drift—whether through human error or malicious intent—requires a shift toward automated auditing and integrity monitoring.

By leveraging Python Scripting for custom audits, utilizing standard Linux Commands for deep inspection, and adhering to strict permission models, administrators can ensure their systems remain secure and performant. Whether you are managing a Linux Cloud instance on AWS Linux or a local Debian Linux workstation, the principles of file system integrity remain the same: trust, but verify (and automate the verification).