The Ultimate Guide to Python Scripting for Automation and System Management

Python has cemented its position as a dominant force in the programming world, extending its influence far beyond web development and data science into the core of modern IT operations. For system administrators, DevOps engineers, and anyone working within a Linux environment, Python scripting has become an indispensable skill. It offers a powerful, readable, and scalable alternative to traditional shell scripting, enabling complex automation, configuration management, and infrastructure orchestration with remarkable efficiency. Whether you’re managing a single Linux server or a fleet of cloud instances, Python provides the tools to streamline your workflows and eliminate repetitive manual tasks.

This comprehensive guide will take you on a journey from the fundamental concepts of Python scripting for system tasks to advanced techniques for remote management and cloud automation. We will explore practical, real-world examples, essential libraries, and best practices that will empower you to leverage Python’s full potential. You’ll learn how to interact with the file system, execute external commands, manage remote servers via SSH, and even interface with web APIs, transforming you from a system user into a system automator.

Section 1: The Foundations of Python for System Tasks

Before diving into complex automation, it’s crucial to understand why Python is often preferred over traditional tools like Bash for scripting and to get comfortable with the core modules that facilitate system interaction.

Why Python Over Bash Scripting?

While Bash scripting is powerful for simple, command-line-centric tasks, it can become cumbersome and error-prone as logic grows in complexity. Python offers several distinct advantages:

- Readability and Simplicity: Python’s clean syntax is easier to read and maintain, especially for team members who may not be shell scripting experts.

- Robust Data Structures: Python has built-in lists, dictionaries, and sets, making it trivial to parse and manipulate complex data formats like JSON or CSV. Doing the same in Bash is significantly more difficult.

- Exceptional Error Handling: Python’s

try...exceptblocks provide a structured way to handle errors gracefully, making scripts more resilient. - Vast Standard Library: Python comes with “batteries included,” offering modules for everything from file I/O and networking to data compression and process management.

- Cross-Platform Compatibility: A Python script written on a Linux machine can often run with little to no modification on Windows or macOS.

Essential Modules: Interacting with the Operating System

Python’s standard library is your primary toolkit. For Linux administration, three modules are fundamental: os, sys, and subprocess.

os: Provides a portable way of using operating system-dependent functionality. This is your go-to for file and directory manipulation, such as checking for existence (os.path.exists()), creating directories (os.makedirs()), and traversing directory trees (os.walk()).sys: Gives you access to system-specific parameters and functions. The most common use case is accessing command-line arguments viasys.argv, allowing you to pass inputs to your scripts.subprocess: The modern and recommended way to run external commands and connect to their input/output/error pipes. It replaces older modules likeos.systemandos.popen.

Practical Example: Finding Large Files

Let’s write a simple script that uses the os and sys modules to find files larger than a specified size in a given directory. This is a common task for a system administrator trying to clean up disk space on a Linux server.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# find_large_files.py

import os

import sys

def find_large_files(directory, min_size_mb):

"""

Finds files in a directory larger than a given size in megabytes.

"""

try:

min_size_bytes = min_size_mb * 1024 * 1024

print(f"Searching for files larger than {min_size_mb} MB in '{directory}'...")

large_files = []

for dirpath, _, filenames in os.walk(directory):

for filename in filenames:

file_path = os.path.join(dirpath, filename)

# Use a try-except block to handle potential permission errors

try:

if os.path.getsize(file_path) > min_size_bytes:

file_size = os.path.getsize(file_path) / (1024 * 1024)

large_files.append((file_path, file_size))

except FileNotFoundError:

# File might be a broken symlink

continue

except OSError as e:

print(f"Error accessing {file_path}: {e}", file=sys.stderr)

return large_files

except FileNotFoundError:

print(f"Error: Directory '{directory}' not found.", file=sys.stderr)

sys.exit(1)

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 3:

print("Usage: python3 find_large_files.py <directory> <min_size_in_mb>")

sys.exit(1)

target_directory = sys.argv[1]

try:

minimum_size = int(sys.argv[2])

except ValueError:

print("Error: Minimum size must be an integer.", file=sys.stderr)

sys.exit(1)

found_files = find_large_files(target_directory, minimum_size)

if found_files:

print("\nFound the following large files:")

for path, size in found_files:

print(f" - {path} ({size:.2f} MB)")

else:

print("\nNo files found larger than the specified size.")To run this script from your Linux Terminal, you would save it as find_large_files.py, make it executable with chmod +x find_large_files.py, and run it: ./find_large_files.py /var/log 50.

Section 2: Practical Automation with Python

With the basics covered, we can move on to more practical automation scripts. A core tenet of Python DevOps is automating repetitive tasks to ensure consistency and save time. We’ll explore creating a backup script and then learn how to properly execute and manage shell commands from within Python.

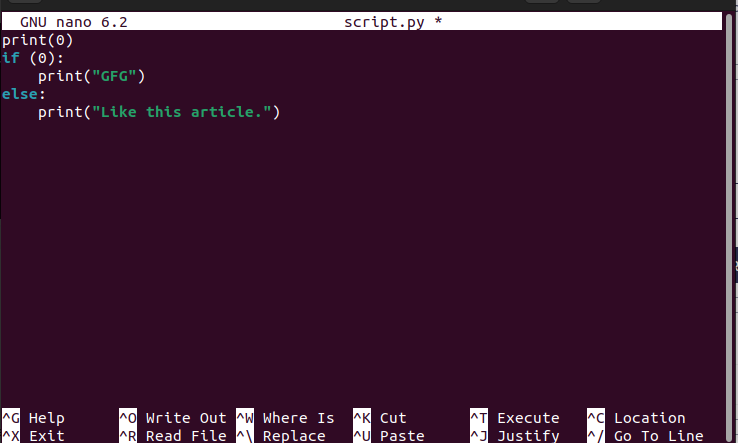

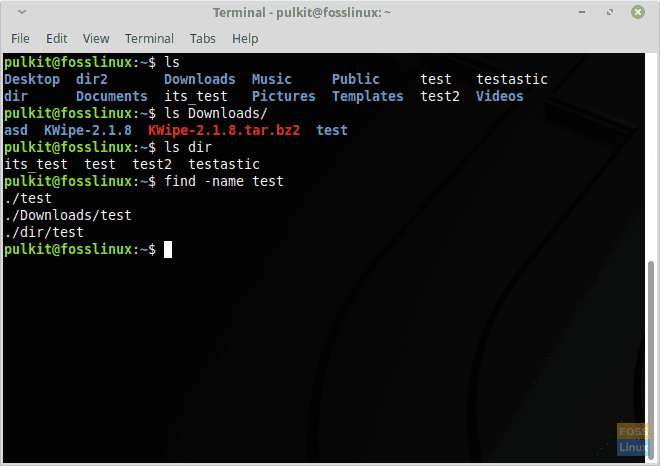

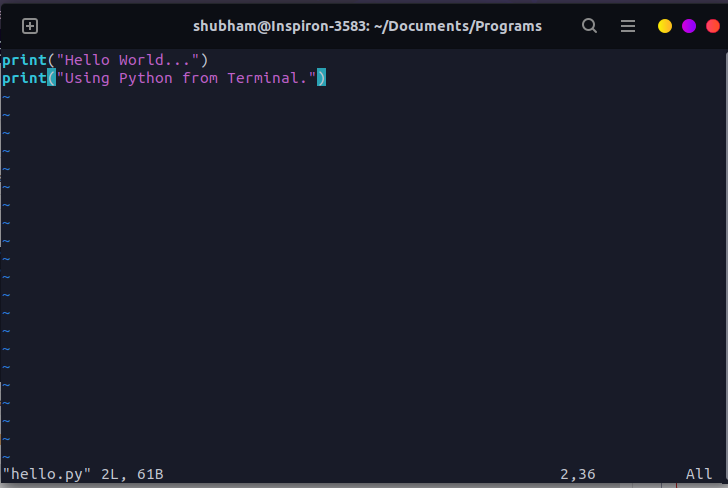

Python script in Linux terminal – How To Save Python Scripts In Linux Via The Terminal? – GeeksforGeeks

Automating System Backups

Let’s create a script that automates the process of backing up a directory by creating a compressed archive with a timestamp. This is a classic system administration task perfect for Python.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# simple_backup.py

import os

import shutil

from datetime import datetime

import sys

def create_backup(source_dir, dest_dir):

"""

Creates a compressed zip archive of a source directory and saves it

to a destination directory with a timestamp.

"""

# 1. Validate paths

if not os.path.isdir(source_dir):

print(f"Error: Source directory '{source_dir}' does not exist.", file=sys.stderr)

return False

if not os.path.isdir(dest_dir):

try:

os.makedirs(dest_dir)

print(f"Created destination directory: '{dest_dir}'")

except OSError as e:

print(f"Error: Could not create destination directory '{dest_dir}': {e}", file=sys.stderr)

return False

# 2. Create a timestamped filename

timestamp = datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d_%H-%M-%S")

source_basename = os.path.basename(os.path.normpath(source_dir))

backup_filename = f"{source_basename}_backup_{timestamp}"

archive_path = os.path.join(dest_dir, backup_filename)

# 3. Create the archive

try:

print(f"Creating backup of '{source_dir}'...")

shutil.make_archive(archive_path, 'zip', source_dir)

print(f"Successfully created backup: {archive_path}.zip")

return True

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error creating archive: {e}", file=sys.stderr)

return False

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 3:

print("Usage: python3 simple_backup.py <source_directory> <destination_directory>")

sys.exit(1)

source_directory = sys.argv[1]

destination_directory = sys.argv[2]

create_backup(source_directory, destination_directory)This script uses the shutil module, which provides high-level file operations. The shutil.make_archive() function is incredibly useful, handling the complexities of creating a zip or tar file in a single line. This script could easily be scheduled with a cron job to perform regular Linux backup operations.

Executing Shell Commands with `subprocess`

Sometimes, you need to run an external command and capture its output. The subprocess module is the standard for this. Let’s write a script to check disk usage by running the df -h command and parsing its output to find filesystems that are nearing capacity.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# check_disk_usage.py

import subprocess

import sys

def check_disk_usage(threshold):

"""

Runs 'df -h' and checks for filesystems with usage above a given threshold.

"""

print(f"Checking for filesystems with usage over {threshold}%...")

# Run the command. text=True decodes stdout/stderr as text.

# capture_output=True captures stdout and stderr.

# check=True raises an exception if the command returns a non-zero exit code.

try:

result = subprocess.run(

['df', '-h'],

capture_output=True,

text=True,

check=True

)

except FileNotFoundError:

print("Error: 'df' command not found. Is this a Linux/Unix system?", file=sys.stderr)

return

except subprocess.CalledProcessError as e:

print(f"Error executing 'df -h': {e.stderr}", file=sys.stderr)

return

lines = result.stdout.strip().split('\n')

high_usage_alerts = []

# Skip the header line

for line in lines[1:]:

parts = line.split()

filesystem = parts[0]

used_percent_str = parts[4]

mount_point = parts[5]

if used_percent_str.endswith('%'):

try:

used_percent = int(used_percent_str[:-1])

if used_percent > threshold:

high_usage_alerts.append((mount_point, used_percent))

except ValueError:

continue # Skip lines that can't be parsed

return high_usage_alerts

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print("Usage: python3 check_disk_usage.py <usage_threshold_percent>")

sys.exit(1)

try:

usage_threshold = int(sys.argv[1])

if not (0 < usage_threshold < 100):

raise ValueError()

except ValueError:

print("Error: Threshold must be an integer between 1 and 99.", file=sys.stderr)

sys.exit(1)

alerts = check_disk_usage(usage_threshold)

if alerts:

print("\nALERT: High disk usage detected on the following filesystems:")

for mount, percent in alerts:

print(f" - Mount Point: {mount}, Usage: {percent}%")

else:

print("\nOK: All filesystem usage is within the threshold.")This example demonstrates key features of subprocess.run(): capturing output, checking for errors, and decoding the result as text. This approach is far more robust than using os.system() and allows your Python script to make decisions based on the output of powerful Linux commands.

Section 3: Advanced Python Scripting for Modern DevOps

Modern infrastructure is often distributed and API-driven. Python automation excels in this environment, with powerful third-party libraries for managing remote systems, interacting with web services, and controlling cloud resources.

Remote System Management with Paramiko

Paramiko is a leading Python library for managing remote servers over Linux SSH. It allows you to programmatically execute commands, transfer files, and manage remote systems as if you were at the terminal.

First, install it: pip install paramiko

Here’s a script that connects to a list of servers and checks their uptime.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# remote_uptime_checker.py

import paramiko

import getpass

def check_server_uptime(hostname, username, password):

"""

Connects to a remote server via SSH and executes the 'uptime' command.

"""

client = paramiko.SSHClient()

# Automatically add the server's host key (less secure, fine for demos)

client.set_missing_host_key_policy(paramiko.AutoAddPolicy())

try:

print(f"\nConnecting to {hostname}...")

client.connect(hostname, username=username, password=password, timeout=10)

stdin, stdout, stderr = client.exec_command('uptime -p')

uptime_output = stdout.read().decode().strip()

error_output = stderr.read().decode().strip()

if error_output:

print(f" Error on {hostname}: {error_output}")

else:

print(f" Uptime for {hostname}: {uptime_output}")

except Exception as e:

print(f" Failed to connect or execute on {hostname}: {e}")

finally:

client.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

servers = ['server1.example.com', 'server2.example.com', '192.168.1.100'] # Replace with your servers

user = input("Enter SSH username: ")

# Use getpass to securely prompt for the password without echoing it

pwd = getpass.getpass("Enter SSH password: ")

for server in servers:

check_server_uptime(server, user, pwd)Note: Using passwords directly is not recommended for production. Best practice involves using SSH keys. Paramiko fully supports key-based authentication.

Interacting with Web APIs using `requests`

Many modern services, from monitoring dashboards to cloud providers, expose a REST API. The requests library is the de facto standard for making HTTP requests in Python.

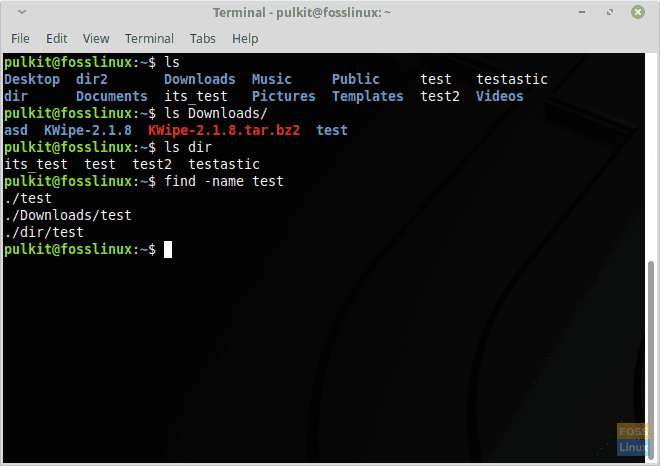

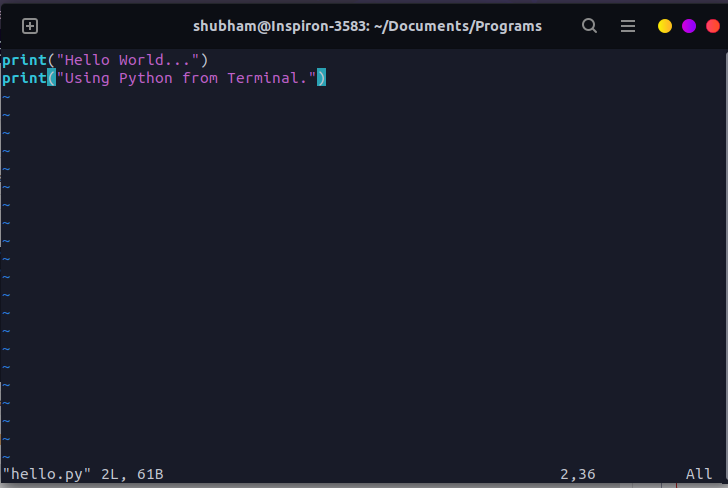

Python script in Linux terminal - How to use the Linux Find Command on Terminal | FOSS Linux

First, install it: pip install requests

This example script checks the health of a web application by querying its health-check endpoint.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# service_health_check.py

import requests

import time

def check_service_health(url, timeout=5):

"""

Performs a GET request to a URL and checks for a 200 OK status.

"""

try:

response = requests.get(url, timeout=timeout)

# A status code of 200-299 is generally considered successful

if response.ok:

print(f"[{time.ctime()}] SUCCESS: Service at {url} is UP. Status: {response.status_code}")

return True

else:

print(f"[{time.ctime()}] FAILURE: Service at {url} is DOWN. Status: {response.status_code}")

return False

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

print(f"[{time.ctime()}] FAILURE: Could not connect to {url}. Error: {e}")

return False

if __name__ == "__main__":

# A list of services to monitor

services_to_check = [

"https://api.github.com/status",

"http://example.com",

"http://a-service-that-is-down.local"

]

for service in services_to_check:

check_service_health(service)

print("-" * 30)This type of script is invaluable for system monitoring and can be integrated into alerting systems to notify administrators of downtime.

Section 4: Best Practices for Robust and Maintainable Scripts

Writing a script that works is one thing; writing a script that is reliable, secure, and easy for others (or your future self) to understand is another. Adhering to best practices is crucial for professional Python scripting.

Code Quality and Readability

Always follow the PEP 8 style guide for Python code. Use meaningful variable names, write clear comments for complex logic, and break down large scripts into smaller, reusable functions. A clean, well-documented script is easier to debug and maintain.

Error Handling and Logging

Never assume a command or operation will succeed. Wrap potentially problematic code (like file I/O or network requests) in try...except blocks to handle exceptions gracefully. Instead of using print() for status messages and errors, use the built-in logging module. It allows you to control the verbosity of your output, direct messages to files or system logs, and add valuable context like timestamps.

Python script in Linux terminal - Open and Run Python Files in the Terminal - GeeksforGeeks

Managing Dependencies with Virtual Environments

Avoid installing Python packages globally. Use Python's built-in venv module to create an isolated environment for each project. This prevents dependency conflicts and makes your project's requirements explicit.

To create one: python3 -m venv my-project-env

To activate it on Linux: source my-project-env/bin/activate

Making Scripts Executable

For scripts intended for use in a Linux Terminal, always include a "shebang" line at the very top: #!/usr/bin/env python3. This tells the shell which interpreter to use. Then, make the script executable using the command: chmod +x your_script.py. Now you can run it directly with ./your_script.py instead of python3 your_script.py.

Conclusion: Your Journey with Python Automation

We've journeyed from basic file operations to advanced remote system management, demonstrating how Python scripting is a transformative skill for anyone in Linux administration, system monitoring, or DevOps. Python's clear syntax, powerful standard library, and a rich ecosystem of third-party packages provide a robust platform for automating nearly any task imaginable.

By replacing manual, error-prone processes with reliable, version-controlled scripts, you not only increase efficiency but also build a more stable and predictable infrastructure. The examples provided are just the starting point. The next step is to identify the repetitive tasks in your own workflow and start automating them. Whether it's managing users, configuring an Nginx web server, or orchestrating Docker containers, Python is the tool that will help you get it done.