I checked my server logs this morning. Just a quick glance at /var/log/auth.log while waiting for the coffee to brew. In the span of four minutes, I saw 300 attempts to login as “root”, “admin”, and—weirdly enough—”oracle”.

It’s January 2026. We have self-driving taxis and AI that can write poetry (badly), yet the internet is still awash in bots trying to brute-force SSH with the same password lists from 2015. It’s noisy, it’s annoying, and if you’re lazy with your config, it actually works.

Most people spin up a Linux box, maybe a VPS or a Raspberry Pi, and leave the SSH daemon running with the default settings. They think, “Who’s going to find my IP?”

Everyone. Everyone will find it. Shodan found it before you even finished running apt update.

I’ve spent the last decade cleaning up after breaches that happened solely because someone left password authentication enabled or used a default user account. So, I’m going to walk through how I actually lock down SSH. No “best practices” fluff—just the stuff that stops you from getting owned.

Kill Passwords. Seriously.

If you take nothing else from this rant, take this: Disable password authentication.

Passwords are the weakest link. Users pick bad ones. Defaults are known (looking at you, certain penetration testing distros with “toor” as the root password). Even a strong password can be brute-forced eventually, or leaked, or typed into a phishing site.

SSH keys are mathematically superior. But don’t just generate any old key. I still see people using RSA 2048. Stop it. It’s slow and the keys are massive blocks of text that look ugly in your authorized_keys file.

I switched to Ed25519 years ago. It’s elliptic curve, it’s fast, and the public keys are short enough to fit on a single line of a terminal without wrapping three times. Plus, with the rise of quantum computing concerns (yeah, I know, we’ve been hearing about “Q-Day” for years, but still), modern OpenSSH versions prefer hybrid algorithms like sntrup761x25519-sha512.

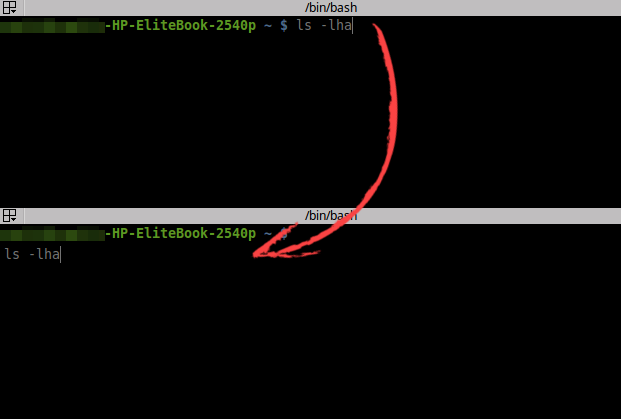

Here is how I generate keys now. I don’t mess around with the defaults:

ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "laptop-2026-jan" -f ~/.ssh/id_ed25519_prodOnce you copy that ID to the server, go into your config and turn off the password ability. If you don’t do this, having a key doesn’t matter because the attacker can just bypass it by guessing the password.

The Config File Diet

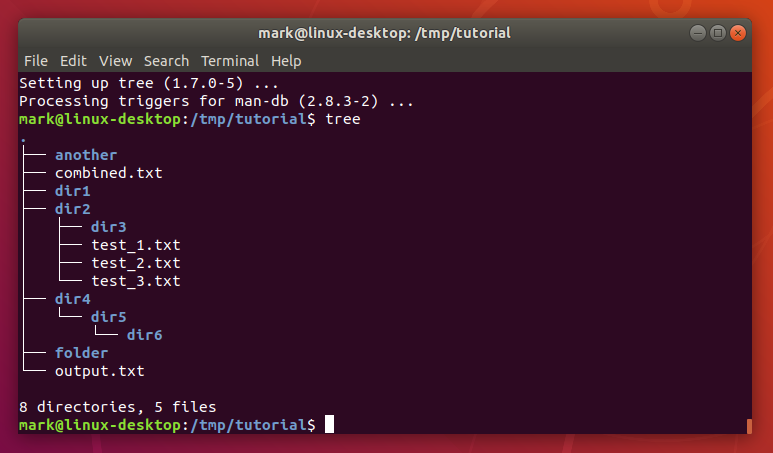

The default sshd_config file on most distros is too permissive. It tries to be compatible with everything, including that ancient FTP client your boss refuses to update. I strip it down.

Open /etc/ssh/sshd_config. Here are the lines I change immediately. If they aren’t there, I add them.

# Disallow root login entirely. Log in as a normal user, then sudo up.

PermitRootLogin no

# Kill password auth dead.

PasswordAuthentication no

ChallengeResponseAuthentication no

# Only allow specific users. This is a lifesaver.

# If I create a 'test' user for a database, it shouldn't have SSH access.

AllowUsers myuser anotheradmin

# Disconnect idle sessions.

# There's nothing worse than a stale root shell left open on a coffee shop wifi.

ClientAliveInterval 300

ClientAliveCountMax 0I once had a junior dev argue that PermitRootLogin without-password was fine. “It only allows keys!” he said. Sure. But it also tells an attacker exactly which username to target. If I disable root login, they have to guess my username and have my key. Why give them half the puzzle for free?

The “Security Through Obscurity” Argument

Let’s talk about changing the default port (22). People get really heated about this.

“Changing the port isn’t security! A port scan will find it in seconds!”

You’re right. It’s not security. It’s noise reduction. Remember those 300 log entries I mentioned earlier? If I move SSH to port 4522, those logs drop to near zero. The automated scripts scanning the entire IPv4 range usually just hit port 22 and move on. They’re looking for low-hanging fruit.

I change the port on every personal server I own. Not because I think it makes me unhackable, but because I like clean logs. It makes it easier to spot when someone is actually targeting me specifically.

MFA: Because Keys Can Be Stolen

I’m paranoid. I assume my laptop might get stolen, or malware might snag my private keys. If an attacker gets my key, they have access. Unless I add a second factor.

For a long time, setting up Google Authenticator (TOTP) on SSH was a pain. You had to mess with PAM modules and it always felt fragile. It’s gotten better, but honestly, in 2026, I prefer using FIDO2 hardware keys (like YubiKeys) directly supported by OpenSSH.

Since OpenSSH 8.2 (which feels like ancient history now), you can generate “resident keys” that require a physical tap. It’s magic. The private key isn’t just a file on disk; it requires the hardware token to be present.

ssh-keygen -t ecdsa-sk -O resident -f ~/.ssh/id_yubikeyIf you don’t have a hardware key, stick to the PAM Google Authenticator method. It’s better than nothing. Just remember to edit /etc/pam.d/sshd carefully, or you’ll lock yourself out. I’ve done it. Walking into the server room (or logging into the cloud console web terminal of shame) to fix a PAM config is a rite of passage.

SSH Agent Forwarding: The Silent Killer

Here is a scenario that happens constantly in dev teams. You SSH into a bastion host (jump box), and from there you SSH into the production database server. To make this work, you use Agent Forwarding (ssh -A).

This is dangerous. If the bastion host is compromised—say, a rogue admin is dumping memory or there’s a rootkit—they can hijack your forwarded agent socket. They can’t steal your key file, but they can impersonate you on any other server that accepts your key as long as you are connected.

Instead, use ProxyJump. It’s cleaner and safer. The crypto happens on your local machine, passing through the jump box without exposing your agent.

In your local ~/.ssh/config:

Host internal-db

HostName 10.0.0.50

User admin

ProxyJump bastion.example.comNow you just type ssh internal-db. It bounces through the bastion securely. No agent forwarding required. I don’t know why tutorials still recommend the -A flag. It should be deprecated.

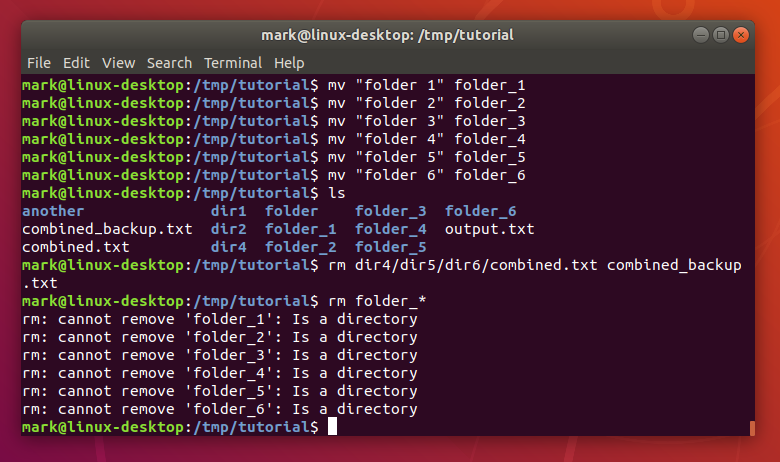

Fail2Ban is Mandatory

Even with keys and non-standard ports, you want an active defense. Fail2Ban (or CrowdSec, which is gaining traction) monitors logs and updates firewall rules dynamically.

If someone fails to authenticate 3 times? Ban their IP for an hour. If they do it again? Ban them for a week.

I usually set the “findtime” window pretty large. Brute-force bots have gotten smarter; they don’t hammer you 50 times in a second anymore. They try once, wait ten minutes, try again. They try to fly under the radar. So I configure Fail2Ban to look at the last 24 hours of logs.

[sshd]

enabled = true

port = 4522

filter = sshd

logpath = /var/log/auth.log

maxretry = 3

findtime = 86400

bantime = 604800That bantime is one week. I have zero patience for unauthorized access attempts. If you mess up your password three times, you can wait.

When to Use Certificates

If you are managing five servers, SSH keys are fine. If you are managing 500, managing authorized_keys files becomes a nightmare. You have to rotate keys when people leave, distribute new ones when they join… it’s a mess.

This is where SSH Certificates come in. It’s like SSL/TLS but for SSH. You have a Certificate Authority (CA). You sign a user’s public key with an expiration date (say, 8 hours). The server trusts the CA, not the individual key.

The beauty of this is that access expires automatically. If an engineer’s laptop gets stolen on Tuesday, you don’t care, because their certificate expired on Monday night. It’s heavy lifting to set up initially—you need a secure vault for the CA key—but for larger teams, it’s the only sane way to operate.

Final Thoughts

Security isn’t a product you buy; it’s a process of being less attractive to hackers than the guy next to you. By disabling passwords, using modern keys, and putting a bouncer like Fail2Ban at the door, you eliminate 99% of the risk.

Don’t be the admin who leaves the default “kali” or “pi” user active. It’s embarrassing, and frankly, you should know better by now.