I broke my laptop’s Python environment three times last year.

The first time, I was trying to install a specific version of PyTorch that conflicted with my system’s CUDA drivers. The second time, I messed up a symlink while trying to get CMake to find the right compiler. The third time? Honestly, I don’t even remember. I just remember the feeling of staring at a terminal wall of red text and realizing I had to wipe everything and start over.

If you work with simple Python scripts, maybe you can get away with venv or Conda. But the moment you step into the messy world of robotics, trajectory optimization, or anything requiring C++ bindings (like PyBind11), you are entering a world of pain. System dependencies clash. Compilers argue. It’s a mess.

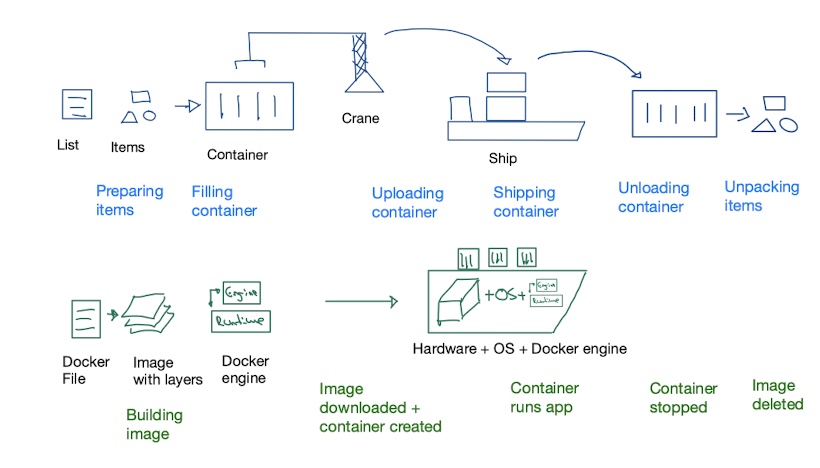

This is where I finally stopped resisting and embraced Docker. Not because I love writing YAML files—I hate them, actually—but because I love being able to delete a mistake with one command.

The “It Works on My Machine” Trap

Here’s the scenario: You find a cool repository. Maybe it’s a trajectory optimizer for a robot arm. It’s got a C++ backend for speed, a Python wrapper for usability, and a Jupyter notebook for visualization. Perfect.

You clone it. You run the setup script. And it fails.

Why? Because the author used GCC 9, and you have GCC 11. Or they assumed you had a specific linear algebra library installed in /usr/local/lib, but yours is in /opt/homebrew. This is the dependency hell that Docker solves. instead of trying to mold your OS to fit the code, you wrap the code in an OS that fits it.

Let’s build a container that handles this exact hybrid mess: C++ compilation, Python bindings, and a Jupyter interface.

Step 1: The Dockerfile

Think of the Dockerfile as the recipe. We aren’t just installing Python libraries here; we need a full build chain. I usually stick with Ubuntu base images for this kind of work because the package repositories are massive.

Here is a setup I use for projects that mix C++ and Python:

# Start with a heavy base because we need compilers

FROM ubuntu:22.04

# Avoid prompts from apt

ENV DEBIAN_FRONTEND=noninteractive

# Install the heavy lifting tools

# We need build-essential for GCC, CMake for building, and git

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y \

build-essential \

cmake \

git \

python3 \

python3-pip \

python3-dev \

&& rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

# Set up a working directory

WORKDIR /app

# Copy requirements first to cache pip installs

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip3 install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt

# Now copy the rest of the code

COPY . .

# If you have a setup.py that compiles C++ extensions, run it here

# RUN pip3 install .

# Default command keeps the container running so we can exec into it

CMD ["tail", "-f", "/dev/null"]A couple of things to notice here. I’m cleaning up the apt lists in the same layer as the install (rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*). This keeps the image size down. Also, notice I’m not running the build command immediately as the CMD. I prefer keeping the container alive so I can jump in and debug if the compilation fails.

Step 2: Docker Compose (Because CLI Flags Suck)

You could run this with a massive docker run command, mapping ports and volumes manually every time. You could also hit your hand with a hammer. Both are painful and unnecessary.

Use docker-compose. It documents exactly how your container should run. This is critical for research code or complex simulations where you need to visualize data.

version: '3.8'

services:

planner:

build: .

image: robot-planner-dev

volumes:

# This is the magic part: sync your local folder to the container

- .:/app

ports:

# Expose Jupyter

- "8888:8888"

environment:

- PYTHONPATH=/app

# If you need GPU support (for ML/Sim), uncomment below:

# deploy:

# resources:

# reservations:

# devices:

# - driver: nvidia

# count: 1

# capabilities: [gpu]

command: jupyter notebook --ip=0.0.0.0 --allow-root --no-browserThe volumes section is the MVP here. It maps your current directory (.) to /app inside the container. This means you can edit your C++ or Python code in VS Code on your host machine, and the changes appear instantly inside the container. No rebuilding the image every time you fix a typo.

Step 3: The Workflow

So how does this actually look in practice? It’s surprisingly boring, which is exactly what you want.

- Build it:

docker-compose build. Go get coffee. This takes a minute the first time. - Run it:

docker-compose up. - Click the link: The terminal will spit out a localhost URL with a token. Click that, and you’re in a Jupyter environment that has all your C++ bindings pre-configured.

If you need to recompile the C++ part because you changed the source code, you don’t need to restart Docker. Just open a new terminal tab:

# Jump inside the running container

docker-compose exec planner bash

# Now you are "inside" Ubuntu. Run your build.

mkdir -p build && cd build

cmake ..

make -j4If the build explodes, it explodes inside the container. Your laptop remains pristine.

The Headache: Permissions and Root

I’m not going to sugarcoat it—Docker on Linux has a massive annoyance with file permissions. By default, the container runs as root. If the container creates a file (like a build artifact or a log), that file is owned by root. When you try to delete it from your host machine later, you get a “Permission Denied” error.

There are two ways to handle this. The “correct” way is creating a user inside the Dockerfile that matches your host UID. The “I’m tired and just want to code” way is to just chmod the files from inside the container if they get stuck:

# Inside the container

chmod -R 777 build/Security pros will scream at me for suggesting that. But if you’re just prototyping a motion planner locally, it saves you an hour of configuration. Pick your battles.

Why This Matters for Complex Systems

I recently worked on a project involving constrained bimanual systems—basically two robot arms trying to move without hitting each other or themselves. The math is heavy. The dependencies are fragile.

Without Docker, sharing that code with a colleague is a nightmare. You spend three hours debugging their environment variables. With Docker, you just say, “Install Docker, run docker-compose up, and look at the notebook.”

It turns “environment setup” from a day-long struggle into a background task. And when you’re done? docker-compose down. It’s like it never happened. No leftover libraries, no modified paths, no broken Python installs.

Trust me. The initial friction of writing the Dockerfile is worth the hours of debugging you save later.