It’s February 2026, and I still see people typing twenty-character passphrases every time they reboot their Linux laptops. Actually, I used to be one of them. There’s something comforting about the “something you know” factor of a massive passphrase, right? It feels secure. It feels like you’re actually doing something.

But honestly? I’m tired. I reboot my machine way too often for that.

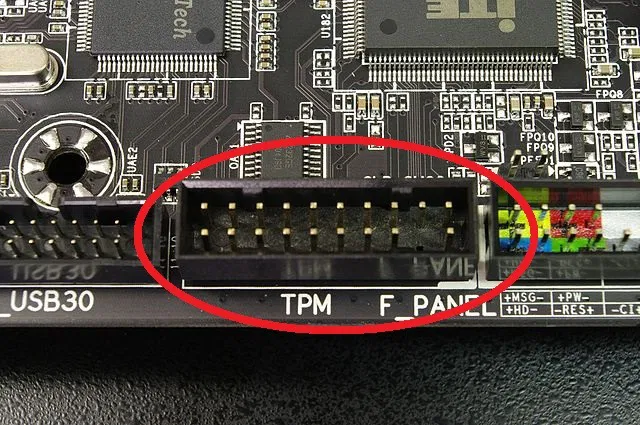

I spent the last weekend messing around with the latest TPM integration in systemd (specifically v259 on my Arch install), and the way we handle disk encryption has shifted under our feet while we weren’t looking. If you’re still managing LUKS headers manually or using ancient scripts to bind keys to your TPM, stop. The tooling has finally matured enough that you don’t need a PhD in cryptography to set up auto-unlocking that actually works.

The Death of the Passphrase (Sort of)

The goal here isn’t to remove security; it’s to shift trust. Instead of trusting your memory, you’re trusting the state of your hardware. And if the bootloader hasn’t been tampered with, the Secure Boot keys are valid, and the kernel creates the expected measurements, the TPM releases the key. But if anything—and I mean anything—changes, the TPM clams up, and you fall back to your recovery password.

I set this up on my Framework 13 (AMD Ryzen 7040 series) running Kernel 6.13.2. It wasn’t exactly smooth sailing at first, mostly because I didn’t understand how strict the PCR policies had become.

Here is the command that eventually worked for me. Note that I’m targeting a specific partition here:

# Enroll the TPM2 device to a LUKS2 slot

# PCR 7 = Secure Boot state

# PCR 11 = Unified Kernel Image (UKI) measurements (if you use them)

sudo systemd-cryptenroll /dev/nvme0n1p3 \

--tpm2-device=auto \

--tpm2-pcrs=7+11 \

--wipe-slot=tpm2A quick warning: Do not run this without a recovery key. Seriously. I almost locked myself out last Tuesday because I was arrogant and thought, “I’ll just add the recovery key later.” No. Do it first. If your motherboard dies or you update your BIOS without prepping, that data is gone forever without a backup passphrase.

PCR Policies: The “Magic” Numbers

The trickiest part of this whole setup is deciding which Platform Configuration Registers (PCRs) to bind against. But don’t bind to PCR 0 or 2 — that’s old advice. If you do that, your disk won’t unlock whenever you update your firmware. The modern approach — and what systemd seems to be pushing heavily now — is relying on PCR 7 (Secure Boot policy) and PCR 11 (Kernel/UKI).

This is where the new measurement APIs come in. The system can now pre-calculate what the PCR values should be for a future kernel. Basically, the TPM doesn’t just check “is the value X?” It checks “is the value signed by a key I trust?”

This means you can update your kernel, and as long as the new kernel is signed by the same vendor (or your own custom keys), the disk still unlocks. No more scrambling to re-enroll keys after a pacman -Syu.

Debugging the “Access Denied” Nightmare

So, what happens when it breaks? Because it will break.

I ran into an issue where systemd-cryptsetup refused to unlock the volume during boot, dumping me into an emergency shell. My heart rate spiked to about 120 instantly. Turns out, I had plugged in a USB drive that had an Option ROM, which subtly shifted the boot measurements just enough to freak out the TPM.

The newer versions of systemd have improved the event log visibility significantly. You don’t have to decipher raw hex dumps anymore. You can pull the measurement log in JSON format, which makes spotting the anomaly way easier.

# Inspecting the current TPM state and logs

bootctl status --json=prettyWhen I looked at the log, I saw an unexpected measurement in PCR 4 (Boot loader) that didn’t match my policy. I pulled the USB drive, rebooted, and it worked. It’s finicky, but that’s the price of security that actually checks the hardware state.

Why Unified Kernel Images (UKI) Matter Here

You can’t really talk about modern Linux disk management without mentioning UKIs. If you’re still using a separate kernel and initramfs floating around in /boot, you are leaving a massive gap in your chain of trust.

With a UKI, the kernel, command line, and initramfs are bundled into a single PE binary. This binary is signed. systemd-stub measures this binary into PCR 11. This is the glue that makes the whole “auto-unlock” thing safe. If an attacker tries to modify your kernel parameters to boot into a root shell (init=/bin/bash anyone?), the measurement changes, PCR 11 changes, and the TPM refuses to give up the disk key.

It’s a beautiful trap.

My Takeaway

Is this setup for everyone? Probably not. But if you take the time to set up UKIs and understand your PCR policies, you can finally say goodbye to that boot password.

Just, please, write down your recovery key. Put it on a piece of paper. Put that paper in a safe. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.